Views from art and science on rice farming changes and biodiversity in Japan.

The light of the firefly has been dimmed by pesticide use over the modern Japanese farm. Artist Isao Miura , a key exhibitor in GroundWork’s Japan Water exhibition, was brought up on a farm, which his nephew still runs. His partner, poet Chris Beckett relates how his work draws attention in a gentle way to the symmetry and balance of the healthy farm. How different and how much more full of fireflies were the old farms. This blog was inspired by 2 articles in The Ecologist in May and July 2020, by Phil Carter relating how pesticide use in Japan’s rice fields is reducing biodiversity (full reference at end).

By Chris Beckett

When Isao Miura was growing up on his family’s rice farm in Akita in the 1950s, he and his younger brother used to collect fireflies that milled in the air around the paddy fields. They would skip around, catching the flies in thin paper bags which became lanterns. The boys would hold the lanterns up and sing the famous song Hotaru no Hikari, which is normally sung at graduation ceremonies and at the end of the school day. It is an old song, a contrafactum written in 1881 to the tune of Auld Lang Syne, the lyrics describing the hardships of an industrious young student studying by the light of fireflies because he has no lamp:

Hotaru no hikari, mado no yuki, Fumi yomu tsukihi, kasane tsutsuItsushika toshi mo, sugi no to wo, Aketezo kesa wa, wakare yuku.

Light of fireflies, moonlit snow by the window. Many suns and moons spent reading. Before one knows it, years have passed. The door we resolutely open; this morning, we part ways.

Countless Japanese woodblock prints repeat the theme of fireflies and how children, even adults, love to chase them.

When Miura returns to visit the family farm and meet his brothers and sisters, not only has the old thatched farmhouse gone, together with its central firepit and fire-ladders hanging from the rafters, but so have most of the fireflies. A few remain, like the butterflies in our gardens, to remind us how magical they were. Like the horses who used to plough and provide manure, and like people, too, who have left to work in cities, so that the countryside now lacks a lot of its old chatter and bustle.

Managing a Japanese Rice Farm – then and now

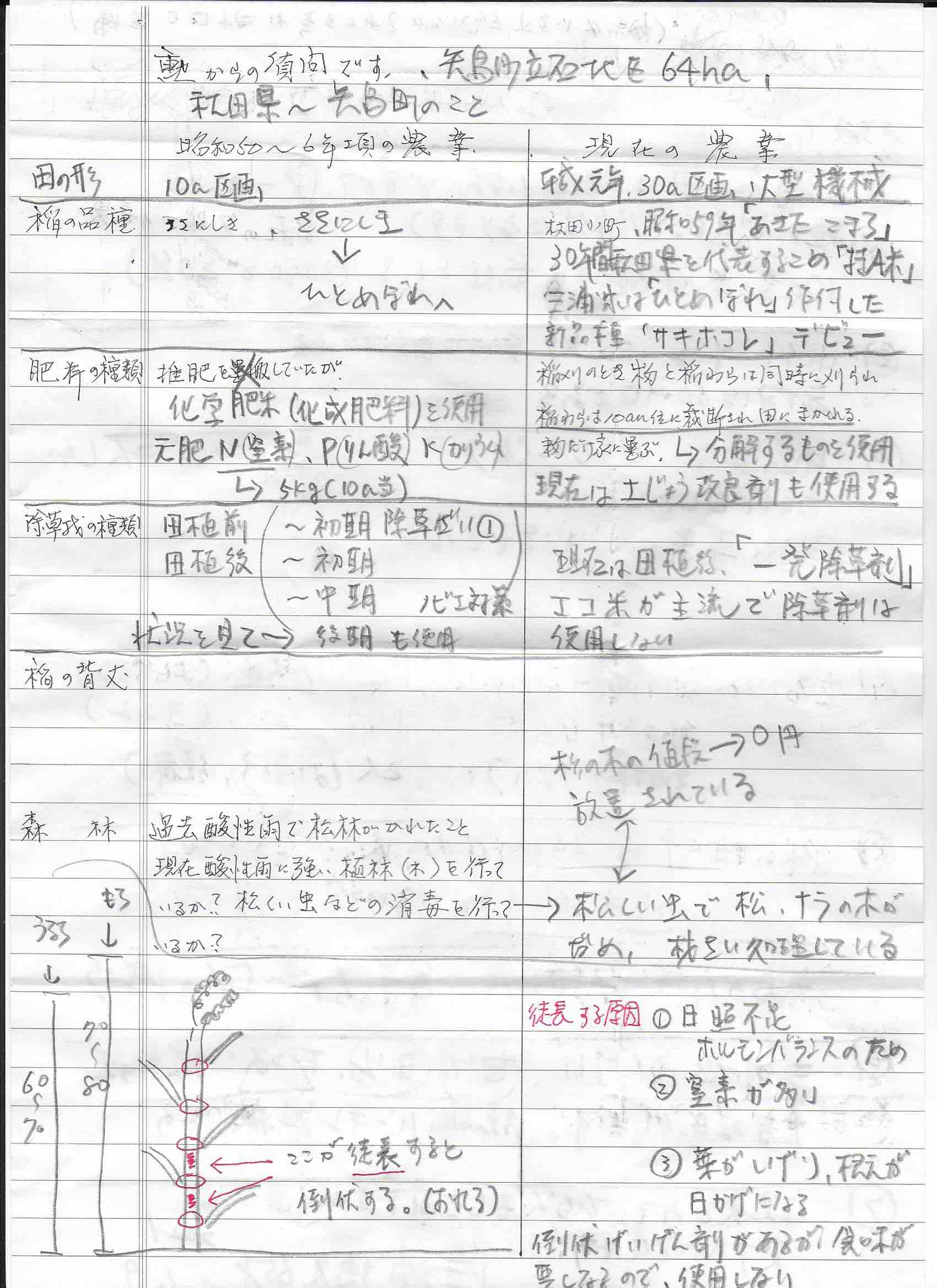

After the death of Miura’s eldest brother, his nephew now owns the family farm. Miura asked him to describe some of the main differences between “then” and “now”. He came back with this 2-column chart.

The chart details for example:

- The tripling in size of fields to accommodate machine planting and husbandry (from 3 ares to 10);

- The old dependance on horse manure and nitrogen in snow, versus chemical fertilizers and potash;

- The change from manually harvesting the whole ripe stalk (for subsequent drying on racks and threshing) to modern machine topping (remainder of stalk is shredded and left to compost with chemical catalyst);

- The move from manual weeding to weed-killers.

But the chart also makes clear that use of fertilisers and weedkillers is declining on the farm for two main reasons, first that they affect the taste of the rice, second they can over-encourage growth at the expense of the health of the plants which demand space, airiness, warm water, light.

In the past, the main variety of rice grown in this area was Sasanishiki, now they grow Hitomebore and Akita Komachi, named after the great Heian era poet and beauty, Ono no Komachi.

This variety is famous throughout Japan for its “delicious taste and superior quality, once freshly cooked it becomes sticky and chewy while still retaining its shape and texture, ideal for moulding into sushi and onigiri rice balls” (so says the product marketing). Quality and taste are becoming as, if not more, important than quantity alone. They are effectively the carrot for reducing chemical dependency and damage to the paddy.

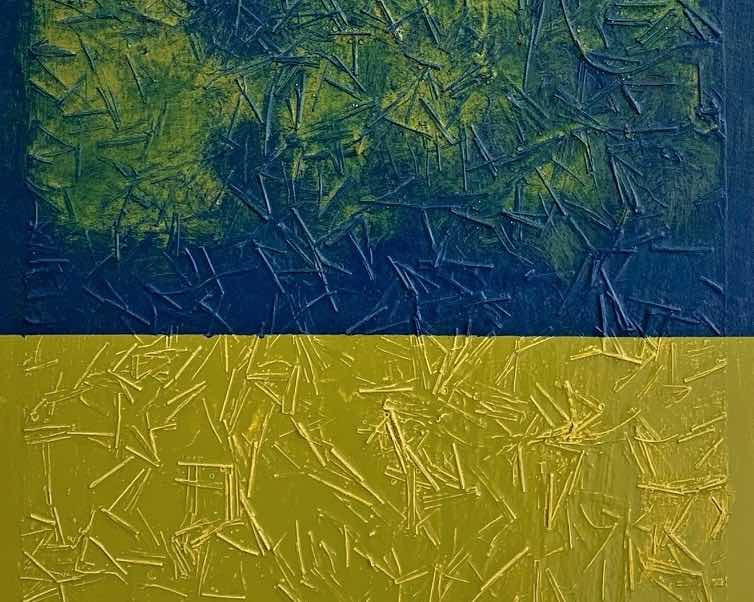

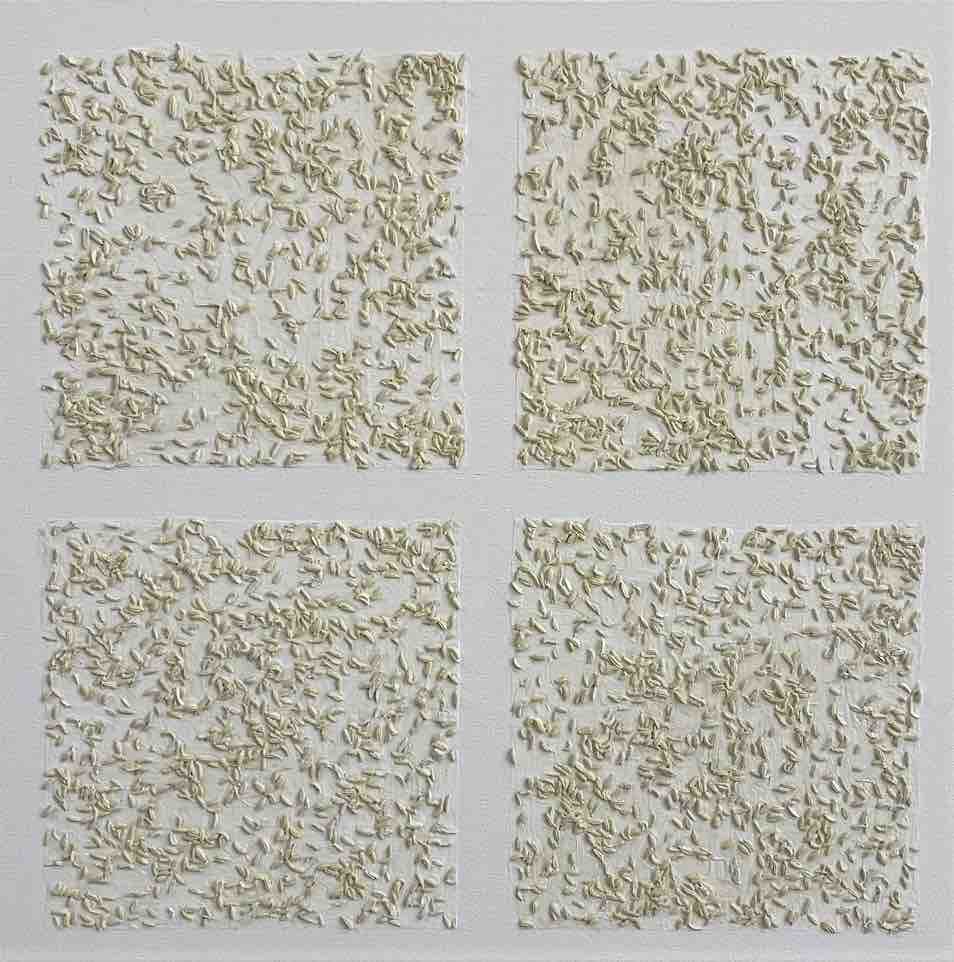

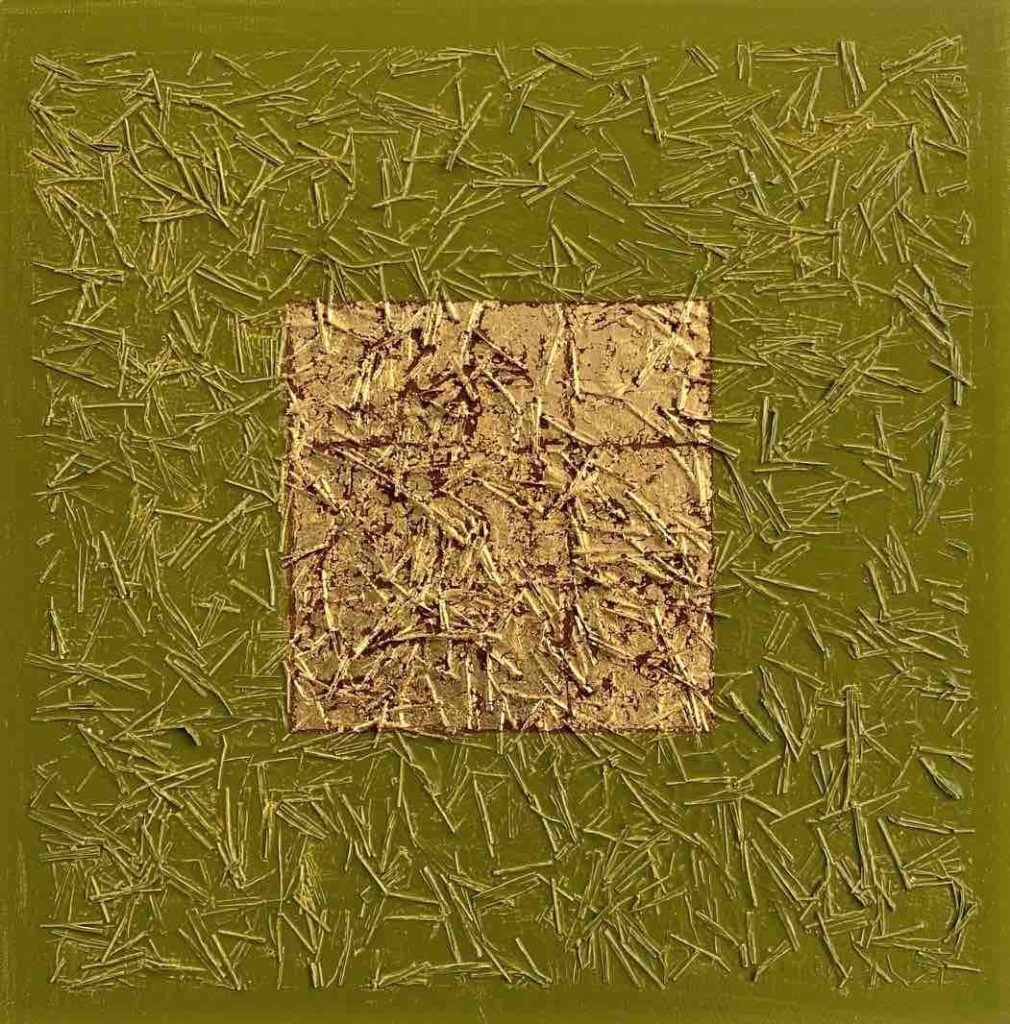

Isao Miura’s Rice Paddy Paintings

Miura’s series of Rice Paddy paintings follow the farming process he knows so well from seed nursery to harvest, but go much further in evoking the seasonal cycle from winter snow-cover, through warm rain (where stalks bowed with rice represent the streams of rain) and sunrise; from the simplicity of shapes and colours to the richness of gold representing the sun but also of the rice itself and its place in Japanese culture and diet.

Having worked in the paddy fields as a young boy – there used to be a special school holiday in May so that farming sons and daughters could help with planting – the viewer can feel the artist’s intimate connection with his materials and subject. There is a feeling of great calm in these paintings, but like the oil paint and gold leaf themselves, this calm overlays a seed/stalk background of riotous profusion and energy. Fireflies only add to this abundance and light up the sky and earth.

The tension between abstract simplicity and physical confusion is also found in Miura’s Wind and Cloud paintings, where the characters themselves seem to act out the drama of the landscape and the natural forces which farmers are still largely affected by. It is a tension, too, between past and present, between innovation and good practice, taste and yield. But Miura seems to be saying that these tensions are nothing new, simply more critical now when there is such high demand made by man of the earth on which we live.

It is easy to get nostalgic, to feel unloosed from the place you were born and grew up, because the changes are so fundemental. It is easy to rant as well, even in painting! but better is to try and understand why these changes have occurred and whether they are irreversible, or indeed do they matter?

Threats to biodiversity

Miura’s nephew in Akita may be reducing his use of chemical fertilisers and weedkillers, but the wider picture in Japan is not necessarily encouraging. As Phil Carter writes in the Ecologist,

“The most well-known and culturally important species characteristic of Japan’s “satoyama”, or traditional rice-farming landscape, are precarious. Two bird species, the oriental white stork and Japanese crested ibis, are the subject of limited reintroduction programs following their extinction in Japan. Many insect species, including the charismatic autumn darter dragonfly and Heike firefly, have also undergone dramatic decline across Japan in recent years.

The implications for the biodiversity of the country’s rice-field ecosystems are grave. To counter this, ambitious goals need to be set for the return of conspicious indicator species across their entire former range, rather than a few designated sites. Like the tiger or panda, these species can act as potent symbols to focus public opinion to conserve the ecosystems they represent.”

Phil Carter, The Ecologist

Miura’s paintings, in reflecting abstract symbols for sun, earth, richness, bio-diversity aim to join this conversation. Not in a strident or hectoring way but quite the opposite, by reducing the elements of his childhood landscape to abstract lines and colours, textures, which reflect the beauty of his materials and of his vision.

A scorched earth approach…

According to Carter, again:

“Japan stands at a crossroads, with competing pressures in the government and society. The Japanese government established the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative in 2010 to encourage conservation initiatives for Japan’s satoyama landscape and share them internationally. However, intense lobbying by pesticide companies trying to keep regulations to a minimum in most areas and conservation restricted to protected areas is working against these efforts.”

Phil Carter, The Ecologist

In another Eologist article he writes that:

Chemical companies are taking advantage of Japan’s weak laws on pesticide use by selling a wide variety of broad-spectrum pesticides for use in rice farming, including neonicotinoids banned in other countries.

But other pesticide types with similarly devastating effects on aquatic ecosystems continue to be sold and promoted, such as Trebon, a synthetic pyrethroid sold by Mitsui Chemicals, and Prince, containing fipronil, a phenylpyrazole sold by BASF… The process of removing dangerous pesticides from use is an arduous one, with companies like Bayer fighting bitterly to continue sales of each product both in court and with campaigns to discredit any critical scientific studies.

In recent years, this scorched-earth approach has led to environmental groups focusing their energies on neonicotinoids, eventually achieving bans on some products in the European Union. According to information provided by Japanese NGO Act Beyond Trust, five main companies, Bayer, BASF and Syngenta from Europe and Sumitomo Chemical and Mitsui Chemicals from Japan, manufacture and sell rice-field insecticides in Japan. With negative publicity surrounding neonicotinoids, Mitsui Chemicals is switching its sales campaign to a different class of insecticide while continuing to quietly sell dinotefuran, its flagship neonicotinoid. “

Phil Carter, The Ecologist

Raising awareness through art

So not only is the loss of fireflies a cause of sadness, it is a warning and “potent symbol” that the biodiversity of the land is under attack. The flip side of this coin is that harmful chemicals not only damage indicator species, they also affect the taste of the rice, as Miura’s nephew attests. Whether through raising awareness in any way that we can, including in art, or through directly changing the way of farming to make it more natural and environmentally friendly (and the resulting product more tasty!), the race is on to re-green and even re-gold the paddy fields of Miura’s childhood.

By Chris Beckett, March 2021

Reference:

Broad-spectrum insecticides in Japan, by Phil Carter, 26th May 2020

https://theecologist.org/2020/may/26/broad-spectrum-insecticides-japan

The Ramsar Convention and Japan’s rice-paddy ecosystems, by Phil Carter, 6th July 2020

https://theecologist.org/2020/jul/06/ramsar-convention-and-japans-rice-paddy-ecosystems#main-content