Veronica Sekules

A boy brushed a Nettle and was stung by it. His mother told him: “It stung you because you brushed it lightly. Next time grasp it boldly and it will be soft as silk and not hurt you.”

A fable attributed to Aesop. The moral? ‘Whatever you do, do it with all your might’.

This spring, thanks to lock-down and fine weather, I am in danger of turning into a weed-bore. Every day for the last two weeks I have been grasping the nettle in the literal sense, painstakingly weeding and pulling out barrow after barrow of roots. I have now made a vast snaky mountain of them ready for burning. I can’t resist a smug feeling of achievement in having bare soil ready for planting and sowing vegetables. But apart from that, it is actually satisfying to clean out strings of yellow nettle and fleshy white bindweed root.

Weeding is altogether a mediative process, solitary and measured. Good thinking time. I am engaging, as I dig, in daily quiet reflection. While I wish it were possible to put the sick wider world to rights, I am trying to do so in my inner world. Grasping the nettle, I suppose, is partly about mental health.

Weeding, cooking and mental health

But this little essay is also about the bigger messages, how mundane daily activity leads to reflection and action. And then, that can have consequences in practice, which in turn can lead to further research. My root digging has led to a re-evaluation of the role of weeds. More specifically, I have looked again at the nettle, cooked it and found out about it. Ultimately, grasping the nettle has been about the moral message from the fable above: doing something with all my might.

The value of bugs and weeds

The current coronavirus lock-down has enabled me to do all this weeding, so it is a benefit of sorts. As well as cleaning the ground, it is good for my mental health. I am indeed very well aware of being lucky in having space. As I dig I do wonder how it is for the poor people who are imprisoned in tiny urban spaces. What can be the equivalent for them, of a meditative ritual like weeding?

There has also been another sort-of benefit. Along with many other people, I have been noticing details of the natural world a lot more. Art has most definitely sharpened my observation, helping me to grasp the nettle in a number of ways. For example, one day I spotted a little green bug crawling about in the soil. I subsequently learned thanks to an Instagram correspondent that it was a stink bug. It reminded me of Cornelia Hesse-Honegger’s beautiful picture of a tree bug near a nuclear power station in SW France.

Human actions can have devastating consequences

Cornelia made the image to record the effects of nuclear radiation. Even at the low levels from an ordinary nuclear plant, this poor bug had suffered deformities. It had one antenna shorter than the other, but otherwise was very similar to my little stink bug. I marvelled at her tenacity in tracking the creature down and in seeing its detail so clearly. Secondly, her immense skill in portraying the tiny creature so accurately, was truly impressive. Thirdly, and above all, it made me reflect on the scale of human damage to the environment.

Our actions can have hidden but nevertheless devastating consequences. This little bug was acting as a warning sign, but it was Cornelia Hesse-Honegger who revealed that. Her assiduous research world-wide into the scale of damage to true bugs from nuclear radiation is immensely important. I watched my little stink bug crawl away and vowed never, ever to poison the soil for any reason. It was another way to ‘grasp the nettle’ in being thoroughly committed to conservation of nature’s diversity.

The hungry gap

We are currently in what is traditionally known in gardening circles as the hungry gap. Nothing in the vegetable garden is ready. And as I didn’t plant much last year, I don’t even have left over kale or cabbages. Anyhow, the notion of a hungry gap has a hollow ring just now. Apparently, even people in relatively privileged situations who are able to afford food, are eking-out leftovers. Either that, or both, queuing for their socially-distanced supermarket turn, or waiting for sought-after on-line delivery slots. I, on the other hand am a bit of a would-be artisanal peasant. Rather than queuing in a super-market, I would rather comb through my garden and seek out edible plants.

Weeding and cooking

While vegetables are at the seedling stage, this is a time to see what other bounty nature brings. So far I have thrown dandelion leaves into salads, and I can confirm that the plant does not deserve its French nickname of ‘pissenlits’ (piss-in-beds). The jury is out on the merits of dandelion chutney. I bought some last year from a dandelion aficionado, but my attempt to copy his, is so far, lamentable. Even pretty disgusting.

My great long-term weedy salad-love is hairy bittercress, about which I posted on Instagram. Hairy bittercress is normally despised as a pernicious weed. But it has real food potential, is in season in early spring and is a much under-rated kitchen ingredient. It is a bit fiddly to prepare, as one has carefully to clip the leaves away from the roots. But it has a delicate slightly lemony flavour and I as have discovered, it is a perfect base for salsa-verde. This is the Italian condiment, otherwise containing capers, gherkins and mustard, and sometimes anchovy, all pureed together. It is normally made with handfuls of parsley, but hairy bittercress, in my view, is better. Delicious alongside fish, it can also dolloped to the side of more or less anything.

Harvesting and grasping the nettle

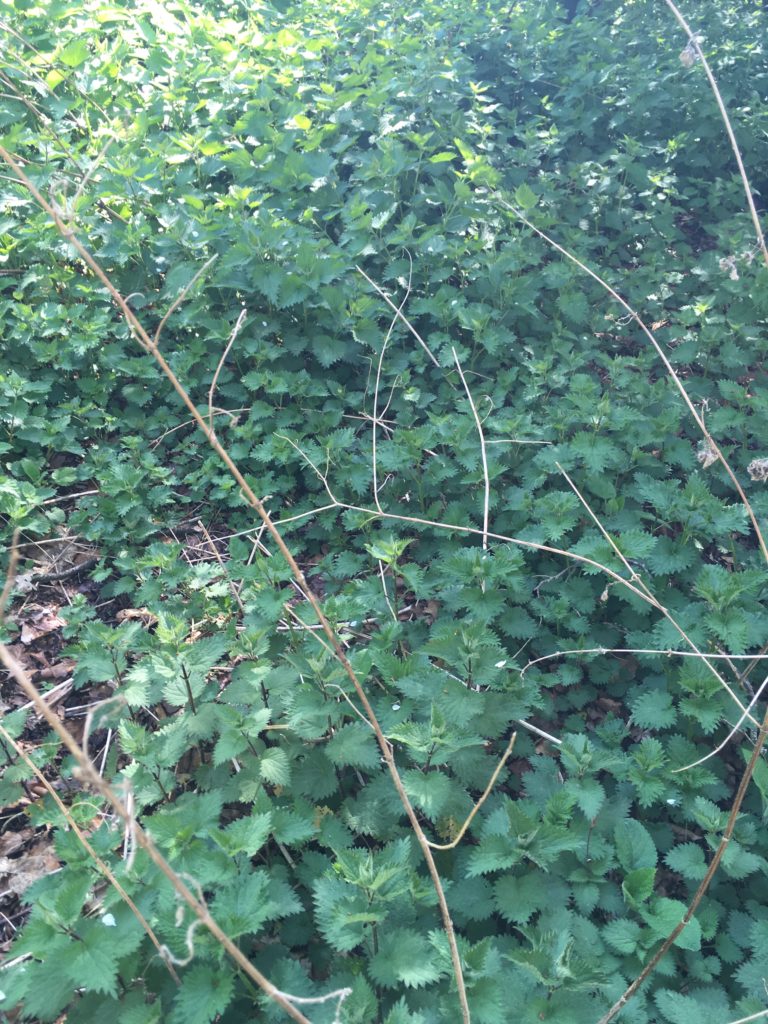

Continuing from the success of bittercress, and the variable virtues of the dandelion, life for me at the moment is all about nettles. Just as I am assiduously digging all their roots out of the vegetable garden, else-where I am delighting in their massively plentiful clumps. I can’t resist harvesting them and trying out all manner of things to do with them in the kitchen. Only the top few leaves are any culinary use however. And in spite of the title of this piece, grasping the nettle, it is very unwise to grasp them without protective rubber or tough impermeable gloves. So armed with my kitchen gloves, basket and scissors, out I go every day to collect a few.

Nettle cooking

Nettle experience is common of course and there is a lot of advice in wild food manuals and on-line, notably from the celebrity forager, Hugh Fearnley Whittingstall.

Most people have tried nettle soup and there are plenty of recipes to be had. Cooked nettles are dryer than spinach, so I prefer to make a them into a puree. I then mix it with miso and cream, both to deepen its savouriness and enrich it. Last week I made nettle bread, based on a recipe for beetroot bread published in Ottolenghi Simple, but with quite a number of substitutions for his ingredients. It is quite cakey, and more savoury than the beetroot one, but delicious toasted and needs no topping. Another dish I adapted from an Ottolenghi origin, is his recipe for a Tunisian ingredient called pkaila . This is normally made from spinach stewed for hours in oil until it becomes blackened, rich and concentrated. I have tried this successfully with nettles to make a condiment for flavouring.

Sweet nettles and beer

My other nettle dish, which has actually been the real triumph, is a sweet green tart. This is based on a traditional sweet chard pie, which I ate years ago in Lucca, where it is a speciality. Eventually, I found a recipe in Leslie Forbes lovely book A Table in Tuscany. Once again, I have adapted it considerably and my recipe is below. My list of things to try next is getting longer as I read more and people tell me more. So, nettle gnocchi is on the way, and there is a recipe in the classic Italian manual, The Silver Spoon. Also nettle pesto, which I make with walnuts instead of pine-kernels. Pancakes are coming, as is frittata and souffle, as all our neighbours keep chickens and eggs are locally plentiful.

My nettle journey has also been about rediscovery. Rootling around in my larder for bottles of elderflower cordial, I came across a small stash of mystery bottles, unlabelled. These turned out to be nettle beer from two years ago. Whereas I remembered it to be a fairly indifferent brew at the time, now it is absolutely delicious. Time is supposed to be one of the greatest ingredients for the home-brewer. But one is always advised to make nettle beer for immediate consumption. However, after 2 years, mine has lost the strangely vegetable-y after-taste that nettle beer often has. Furthermore, it is clear, only slightly bitter, and pretty much like a honey-ed light beer. I wasn’t intending to make any this year, but now I will.

Nettle variety

Back to my digging-thinking and grasping the nettle. Nettles proliferate, and while I always used them a bit, I most definitely regarded them as a nuisance. In fact, I was usually in despair about them. But this year my attitude to nettles has changed absolutely. I have learned more about them. Urtica dioica – is the name of the common stinging nettle, a perennial plant. It was originally native to northern Europe but is now distributed world-wide. There are several sub-species native to Asia, Oceania and the Americas.

But I fancy I can see variations even in my own garden, where some are large and lush, others more delicate. The variety may depend on where they are growing, whether in sun or shade. Nettles are known to grow in previously inhabited, phosphate rich grounds. I see them in unruly profusion under the apple tree where I hang my washing. They encircle the grass in full sun, and yes, they try to colonise the vegetable garden. And don’t even talk to me about flower beds. Nettles embed themselves even where there should be lilies and roses. And I am only slightly exaggerating.

Nettles and health benefits

While I still try to stop nettles from being completely invasive, I feel much more well-disposed to them. Now I see them truly as a benefit, and not only in the kitchen. Their leaves well-rotted make good nitrogen-rich compost, and they are themselves an indication of soil fertility. They are a good habitat for many species of butterflies and moths. Cloth can be made from them, which has a very long history, but also a promising future in the textile industry. Look up their nutritional and health qualities on-line, and you will find a mind-boggling array of benefits. We probably all knew they were rich in iron, evident from the brown colour of the water as you wash them. But they are generally mineral-rich, also containing potassium, manganese, calcium.

For a vegetable they are immensely protein-rich, and contain all the amino acids. They also contain vitamins A, C, K and several B vitamins. They are said to act as antioxidants in the body. This means that they can limit the damage from free-radicals, the agents which cause aging and the spread of cancers. Nettles have long been used in herbal medicine, as an ingredient in creams and potions for treating inflammation, or as a remedy for rheumatism. Nettle tea is supposedly good for treating the kidneys and urinary tract and to help circulation.

Grasping the Nettle again

When I began my digging even a couple of weeks ago, I knew little of this. I was an occasional weed-cook and sometimes used nettles. There were years when I forgot all about them. But through a whole combination of circumstances, this year, my attitude has changed. The artists whose work is currently in GroundWork have taught me to look afresh at nature in general. I mentioned Cornelia Hesse-Honegger’s attention to detail above. But also, Sarah Gillespie’s tender attention to the moth has taught me to be much more sympathetic to them. Alison Turnbull’s example also shows that you don’t have to be an entomologist to be seriously interested in insects.

Diversity and sustainability

The enforced lockdown has also given me a gift of time to devote to seeing things afresh. In filling some of that time, my digging has benefitted my garden, and my mental health. And one consequence was to re-alert me to the nettle, both to its unwanted presence and to its ‘appropriate’ place. In grasping the nettle, I have recognised its usefulness to me and to others. But I have also learned about sustainability and the importance of diversity. Managing the nettle is about taking a positive overview about it as a sustainable resource in my garden. It is about respecting the diversity of nature. Allowing too much nettle, risks it overtaking all other species. But grasping the nettle is different. It is about keeping it in balance, yet thoroughly recognising its value as a sustainable local resource.

Grasping the Nettle: a couple of recipes

Sweet nettle tart

You will need to line a tart tin with short crust pastry of your choice and bake it blind. (First prick the bottom with a fork, then line with greaseproof paper and fill with dried beans and bake for 10 minutes). Lift out the paper and beans and leave it to cool before filling it.

For the filling:

500 gr cooked weight of well-washed, cooked and drained nettle tops

3 tablespoons granulated sugar (keep a little back for sprinkling over the tart at the end of baking)

A handful of pine nuts, or chopped walnuts, or sunflower seeds

A handful of raisins

Grated peel and juice of an orange

1 teaspoon cinnamon

2 tablespoons grated parmesan cheese

2 eggs beaten

Chop the cooked nettle leaves quite finely, then mix all the other ingredients, beating in the eggs last. Pour into the part-cooked pastry case and bake for 25-30 minutes in a moderate oven, or until set. Sprinkle over the granulated sugar immediately as it comes out of the oven. Cool in the tin.

With acknowledgement for the recipe that inspired this, to Leslie Forbes, A Table in Tuscany, Webb and Bower, Exeter, 1985.

Nettle bread

500 gr cooked weight of well-washed, cooked and drained nettle tops

200 gr flour – all wheat, or mixed rye and wheat

2 tablespoons pumpkin seeds, or sunflower seeds

1 tbs honey

2 tsp caraway seeds

2 tsp nigella seeds

150 gr well-drained yoghourt, or cheese made from reduced whey from home-made yoghourt – or use soft goats cheese instead

2 eggs

2 tsp baking powder

a little salt

Chop the nettles finely and mix with nuts and seeds and flour and salt. Using a fork, in a measuring jug or separate bowl, whisk together the honey, yoghourt or whey cheese*, (or soft goat’s cheese) with baking powder and eggs. Immediately mix into the nettle and flour mixture. Spread into an oiled loaf tin and bake for 25 mins at 180, then wrap in foil and bake for 20 mins more. Test with a skewer, which should come out dry. Leave it to rest in the tin for 20 mins, then unmould to cool on a wire rack. Keep in the fridge. It is better the next day & keeps well for a few days.

*I make my own yoghourt so always have a lot of whey which I drain off and reduce to make a cheese & I also often drain the yoghourt itself through cheesecloth to make cheese when I have too much.