15 July – 10 September 2017

Jayne Ivimey, Suky Best, Martin Brandsma, Patrick Haines, Sabine Liedke, Milo Newman, Nessie Stonebridge,

& At the Steel Rooms, Brigg, Lincolnshire,

Bird after Bird featured six artists entranced by the fragility of birds, exploring them in life and death. The exhibition aimed to raise our awareness of birds and of all the dangers they face. But also to recognise the extent to which the artists continue to bring, extraordinary new visions of them. They are helping us to get close to birds. Also, to see them differently, to notice their familiarity and their strangeness.

The exhibition toured to the Steel Rooms, Brigg, and included additional works by Sabine Liedke.

Secret life of birds

It is the fleeting nature of their subject, its elusiveness which is the compelling thing. Birds live among us and yet so much of their life is secret. Even a relatively tame bird is wary of human presence.

Each of the artists spent countless hours researching, watching, waiting for the right moments for birds to appear. Albeit in very different ways, they were constantly thinking about their relationships with their subjects. Using research skills and close observation, they got closer to their different species. But in no case has there been a conventional desire to seek any literal means to portray them. Rather they have all sought a kind of visual poetry of representation.

Jayne Ivimey & The Red List

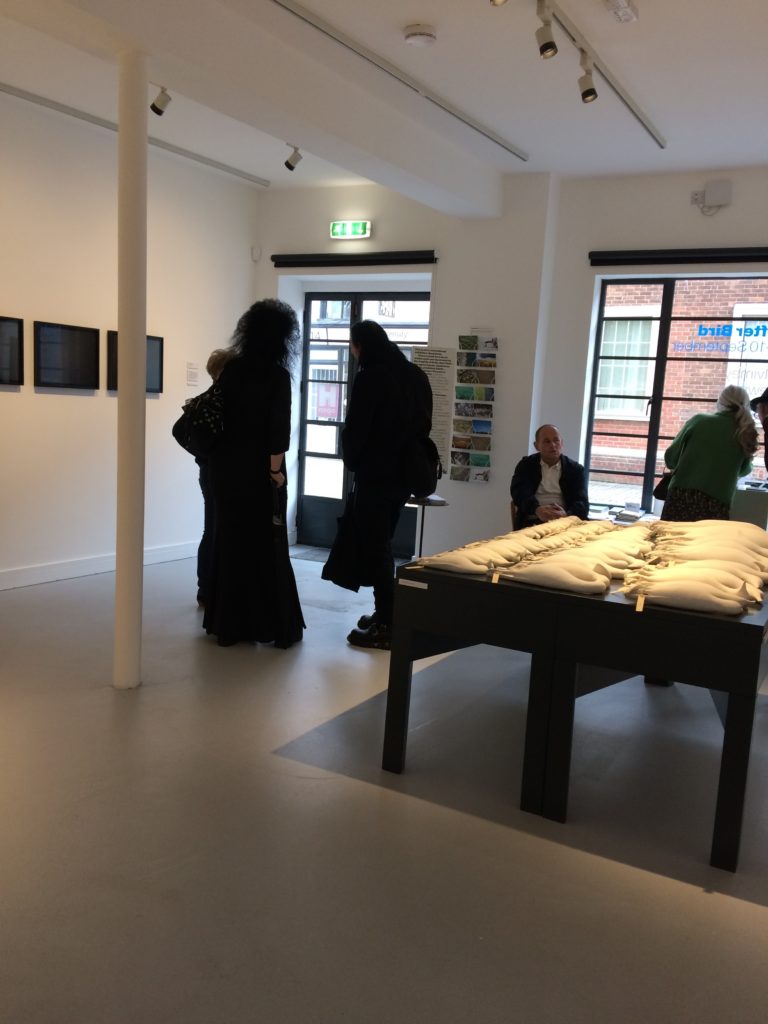

At the heart of the exhibition and giving it its title, is the work of Norfolk-based artist, Jayne Ivimey. The Red List consists of bird species that are threatened and endangered. It grows with depressing speed, day by day.

Jayne presents us with a tribute in the form of an installation of white bisque-fired stoneware effigies of dead birds. They are presented ‘bird after bird’, limp bodied, heads hanging loose in death, wings folded and without purpose. Their feet are crossed over, a label tied to the legs giving the date, name and provenance.

The unravelling tragedy

Jayne’s project involved months and months of research, observation, drawing in archives. She worked at the Rothschild museum in Tring, and Norwich Castle Museum. As she says, “I want to express their beauty and vulnerability as we begin to comprehend the unravelling tragedy” . Her work is timely. In 2018, endangered British birds rose by 20, bringing the total to a staggering 70 birds on the Red List.

“What do 70 dead birds look like and how can we imagine this number? How can we experience the deep sense of loss to our environment and to ourselves?”

Jayne wanted to make a dramatic installation with a phalanx of birds. So we aimed to make it look a bit like a mortuary slab. Something between that and a museum display. Behind the black table. on the wall, was a bank of silver-point drawings, also representing the Red List. Together the assembly was both very moving, and alarming.

Jayne Ivimey: The story leading to Bird after Bird

“During my time working for Meg Amsden and the Broads authority I came across the shocking photographic records of duck shoots with dead coots piled high in village streets for the poor to pick at. As a child I remember the Boxing day shoots on my uncle’s farm with dead pheasants strung in braces over row after row of hooks in the outbuildings and later my mother hunched over in the scullery for hours plucking the birds for a feast. Even then the feathers beguiled me with their wondrous camouflage technique.”

In 2011 while I was working on a dotterel restoration project in New Zealand, there was a terrible disaster in the Bay of Plenty where I lived. A large cargo ship The RENA hit a reef and sank just off my beach spilling thousands of tons of oil and containers into the pristine bay. Toxic chemicals, beefburgers and oil spilled into our life. After the clearup I made 2 little films for an exhibition about the disaster..

The Red List

In 2012 I returned to the UK to be greeted by 16 new additions to the RSPB’s Red list of endangered British birds now totalling 52.

Shocked by this I went to the Natural History Museum to look at them

In their preserved state. The ‘skin’ collection is at the Rothschild Museum in Tring where over three quarters of a million birds are stored in long corridors of drawers representing 95% of the worlds extinct birds .

This shocking site provoked me into thinking about loss and how to explain the sadness I felt

Holding a cuckoo in my hand captured in 1918 in Argyleshire and a Corncrake from Cramond in 1910 was powerful..

The labels told one story after another.

Mouth of the Somme 1913, Gibralter1931 , Pisa 1897

This obsessive capturing and cataloguing of this finite source.

The Norwich Castle museum was different . Conservation was done by bagging specimens in plastic. Connections with supermarket meat processing quickly set me off to the agro chemical world of farming methods .and its effect on habitat. Shifting light reflected on these rows of plastic bags gave the appearance of water drowning the birds inside . The Castle had a very old collection of bird books. One 6 volume set of 1850s -90s by Lord Lilford of Northamptonshire describing the huge numbers to be found all over ‘the Kingdom’ as he called it.

Birds in the ‘skin position’

So now I have made the 52 birds in the skin position , bisque fired them and left them without glaze to remain as ghostly and vulnerable.

Then I thought about their habitat and their feathers and how well they blend and I made a series of pencil drawings of some of them hidden by their miraculous patterning.

I want to express their beauty and vulnerability as we begin to comprehend the unravelling tragedy.

Milo Newman

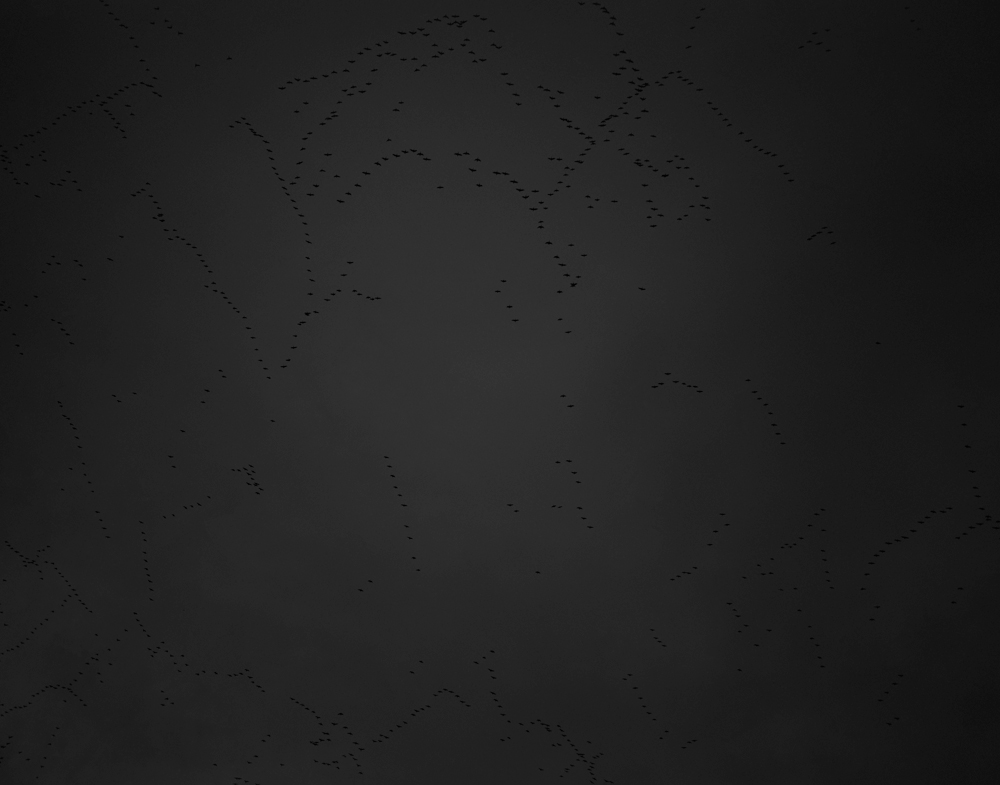

Milo Newman, has spent many hours at dusk photographing pink-footed geese. They migrate each winter to the Norfolk coastline from the Arctic region, Svalbard, Iceland and Greenland. Newman works in the half-light. Then the birds don’t see him, but also because at this time of day, his perception is heightened. He shows the flight patterns of the birds constantly changing, highlighting a sense of freedom:

“With the loss of the light there’s a narrowing of the brilliance of sight, until one is forced to pay the world more attention in order to make out forms. The restriction of vision focuses perception in on specific things. The more attention you give something, the deeper the involvement or connection with it. [This way], one enters into a relationship with it … Through this deep concentration on sensory perception, the physical barrier between the mind and the world dissolves. The mind has a way of leaking out from the body, mingling with the world around it.”

Milo Newman

Empathy with another way of being

Black against black, his images show the arcs of movement, as the birds complete their almost secret feeding rituals. The making of these images is an unutterable experience, a fleeting moment expressing a force. His purpose is not to provide documentary evidence, but to achieve ‘sort of joining with things’. He wants a sense of structure within a process of flux. More so, to find empathy with another way of being, paying it close attention.

“Each day in the winter the geese take off from communal roosting sites out on the marshes or mudflats and fly inland to feed in the fields. At dawn this process is done in small family groups, but at dusk when they return, these groups conjoin to form vast skeins formed of thousands of individuals, stretching outwards, sometimes for miles, the shape, the lines, shifting and changing.”

Patrick Haines

Sculptor Patrick Haines MRBS, is based at Spike Island artist studios in Bristol. Using a diverse range of materials and found objects, his artworks explore alliances between the natural and man-made world. These are often unsettling. At first glance, his compositions seem uncontentious and almost straightforward but, on closer inspection, reveal eerie content and disturbing narratives.

Nature becomes menacing

Birds, pecking at test-tubes and books, appear to be attacking the body of scientific knowledge. It is this knowledge and context which both traps and frees them. Hints of death, spirituality and references from myth weave subtly and consciously throughout his artworks. Nature becomes a little bit creepy and menacing. For example, the ominous waiting movement of ravens caught tantalisingly in bronze.

“Interior spaces are colonised by insects and birds, while constructions in blackthorn and hawthorn bristle with menace.”

The artist

Haines trained in horticulture before studying fine art at North Staffs College of Art. Currently he is a lecturer in Sculpture at Bath Spa University. Haines’s past work includes special effects work, for Spitting Image, BBC wildlife and Aardman animations. He also worked at Arteffects, London, sculpting to commission for other artists, including Antony Gormley, David Mach, Mark Quinn.

Suky Best

Artisancam originally commissioned the film, “Observation of Flight” in 2010. It is one of the fruits of Suky Best’s academic research, for an MPhil, on experiments with movement of birds in early film. It begins and ends on black. Then it turns to blue and white as a flapping bird conducts its life’s journey trapped in an endless loop.

Observation of flight

Suky presents the piece as a fragment, referencing the bird studies of French doctor and physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904). He was part of a pioneering circle of scientists interested in phenomena of movement and its representation. It was really Marey, foremost among them with his bird studies, which led him to experiment with cinematography. Ultimately it led to the development of the cinema camera.

“It plays over and over. A fragment of film, alluding to something much longer. The whole life of a bird spent inside a box at the behest of the scientists observing it. Although the bird is small it takes up the entire area, and can move in any direction.

Suky Best

Nothing else can or will use this enclosure.”

The artist

Suky, based in London, works with print, animation and installation. Many organisations have commissioned her films, including Channel 4, Arts Council, Film and Video Umbrella. She teaches regularly at various art schools including the Royal College of Art and Central St Martins.

Suky exhibits nationally and internationally, formerly at Baltic, Gateshead and Tate Britain. She jointly won the first prize for the John Kobal Photographic Portrait Award. Also she won the International Award for Photography at the National Portrait Gallery in London, among numerous others.

Martin Brandsma

‘During winter, the Schaopedobbe nature reserve in the northern Dutch province of Friesland is inhabited by a single Great Grey Shrike (Lanius excubitor). Unaccompanied by other members of its species, it spends the winter there alone. It appears space is lacking for more Great Grey Shrikes; the Schaopedobbe is only a small feeding territory. The Sentinel, as the Great Grey Shrike is also known, is well acquainted with Martin Brandsma, a keen observer like the bird itself. Brandsma followed this Shrike faithfully from its arrival in autumn 2015 until it left the area in mid-April 2016 to breed in Scandinavia.’

The great grey shrike

Dutch artist Martin Brandsma has created an entire series of work, focusing on a single bird. It is the scarcely seen Great Grey Shrike. Brandsma’s fascination with the Shrike has extended to studies of their feeding, their rituals, their sounds. He made his own empathetic performance in Lapland, with eyes painted black like a Shrike, leaping into a tree. He was chattering like the bird, alert to signs of prey, peering over landscape.

His “Identities” collection features 152 different morphological drawings of the Shrike. These highlight their differences, both from a scientific standpoint and as unique, individual birds. He devised this systematic, minutely observed drawing method to enable a detailed record of presences. They relate to bar codes and DNA profiles. As he says, “our identity is nowadays increasingly constructed and registered on the basis of printing, bar codes and biometrics.”

Tijs Goldschmidt (transl Sherry MacDonald), 2016:

“If you look carefully, you will notice that nothing is the same, that everything has its own identity. What looks at first glance like a series of identical images appears, on closer inspection, to contain an abundance of variations.

”

The artist

Brandsma graduated with honours from Academy Minerva for Arts and Design, Groningen. Since 2012 he has exhibited frequently in the Netherlands and internationally. He shows with Johan Deumens, Amsterdam. Also he was nominated for the Ronmandos Young Blood Award in 2012.

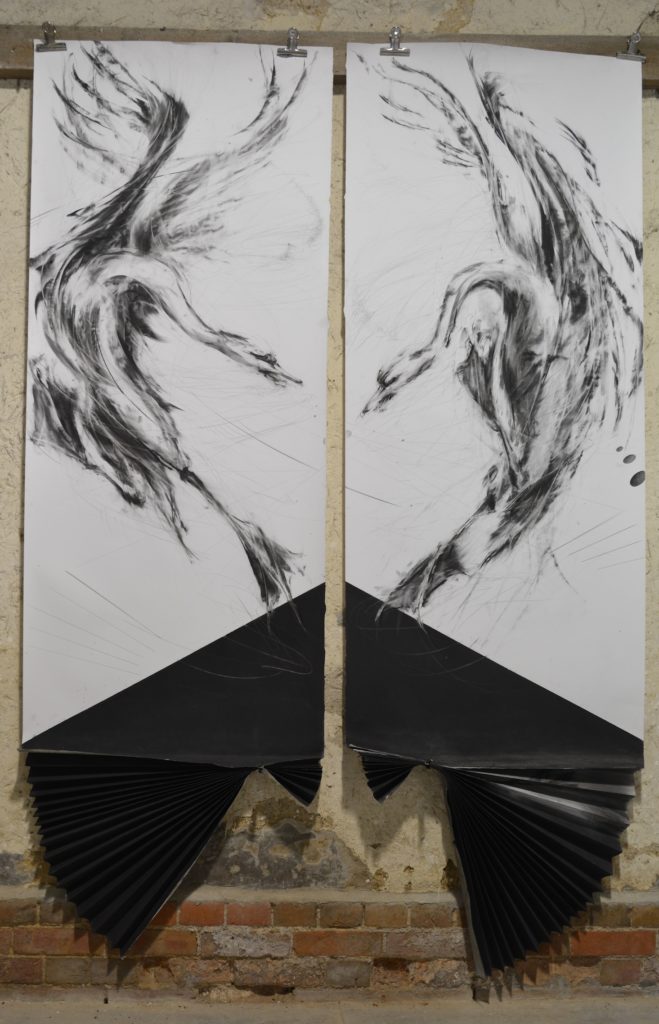

Nessie Stonebridge

Nessie Stonebridge’s art depicts wild birds paused in crystalised units of time, their wings, talons and beaks contorted in frozen muscular action. Her brooding charcoal drawings and electric oil paintings capture the intensity of the bare life of animals.

“Every day I feel compelled to explore the Wet Woods where the Rooks, Woodpeckers, Barn Owl and Tawney Owls are all vying for their territory. The studio looks out onto a very large pond which provides a feeding place to a group of Mute Swans who visit most days…I feel honoured by their visits.”

The fury of beaks

Nessie Stonebridge’s paintings have for many years drawn inspiration from the wild and wind-battered Norfolk coastline. She paints the enormous range of lurid colours in nature, balancing movement and structure. At the heart of her series of swan paintings, is the fury of beaks, encircled by fanlike, semi-abstracted wings. The result, she says, is an aviary of attack and defence. It has grandeur in this case, but is intimating the basic fight-or-flight behaviour of all birds.

Evidence of mortality

Stonebridge’s work draws on observations from life. She lives on a bucolic farm in Norfolk, her studio surrounded by fields, water, and avian passers-by. Nature here is torrid and calamitous. Recently, she spotted a swan with its head chopped off; nearby was a dead fox. It is the brutality of this encounter that fascinates Stonebridge, not the folksy obscenity that it conjures. She is intrigued by the possibility of witchcraft or animal sacrifice in modern Norfolk. The dead swan and fox are evidence of mortality, of everyday death in the animal kingdom. It is this mortality that excites Stonebridge’s imagination.

Vortex-like works

While her vortex-like works appear to spin out into space, it is their slowness that is, perhaps, fundamental. Her painting and drawing process involves a durational labour of accretion and deletion. She applies paint or charcoal, removes and layers it, expending hours and weeks in a meditative focus on line, form or colour. Her works are ultimately the work of a walker, maker and observer. Stonebridge, like the rest of us, seems to love birds because they live and die at a velocity that we can only marvel at.